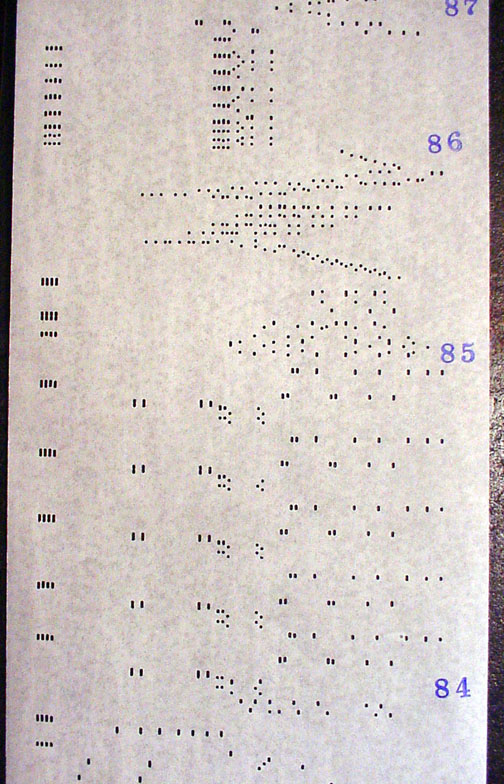

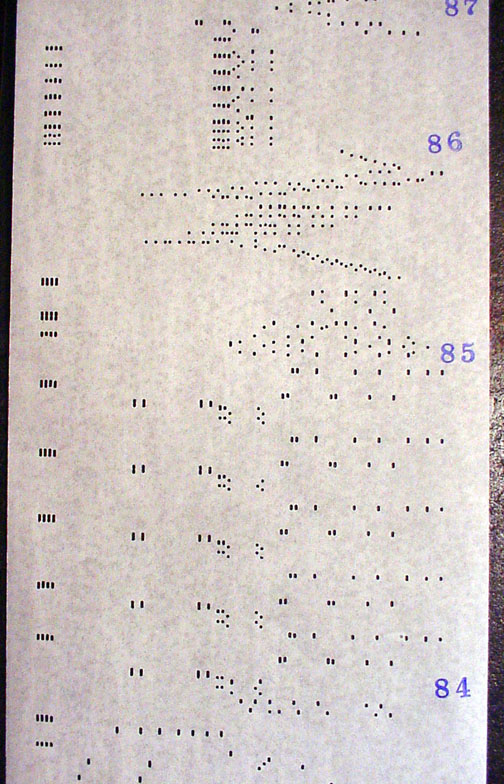

If you had any doubts that BALLET MECANIQUE was conceived as anything other than a "machine performance" combining a Player-Piano and a motion picture projector, this illustration should provide the proof!

Only a movie film, rapidly shifting from scene to scene, could impose such rapid changes upon a musical performance. The Pleyel score 'ties' the music to numbered "TIME SPACE" musical blocks. The ARTCRAFT edition has as many "TIME SPACE" stamps as possible on the second revision of the Set originally created for Swedish TV-Radio, for their motion picture shown with the accompaniment of 2 matched Aeolian pneumatic players, in 1991.

Naturally, as the Vitaphone, Movietone and other sound processes pushed the "art" and novelty of creative silent film accompaniment aside, George Antheil — a true master at reinventing himself and redefining his artistic goals — latched on his sole 'claim to fame', BALLET MECANIQUE, and followed its path into the concert hall. These performances usually eliminated the silent movie. The composition in its recycled form was usually burdened with visual gimmicks (such as aeroplane propellors) and sound effects, most borrowed from the litany of silent movie effects built into the Fotoplayer© instruments. The orchestral performances after 1926 struggled under a multitude of configurations and revivals. Composer Antheil, who referred to BALLET MECANIQUE as a "chamber work" (no doubt a reference to its audio-visual Salon performance beginnings), complained for decades afterwards about the "lack of synchronization" brought on by the many live musicians which were required for the orchestrated revisions.

Here, we can see that the pneumaic player action will leap from one motif to another, as the Pianolist "Follows the Action" — to quote a line stamped on Picturrolls©, viz. the 88-Note rolls for the Player-Piano/Organ screen accompaniments of the day, cut by the Filmmusic Co. in Los Angeles for many years. [Movie accompaniment rolls rarely had Tempo settings on them, since the operator watched the screen and adjusted the tempi accordingly.]

The "sychronization" problem of multiple musicians and instruments remains to this day one of the aesthetic losses whenever an orchestral presentation is given. In the Fall of 1999, there was a BALLET MECANIQUE performance, hyped as "the original version", which featured 16 solenoid players operating on the MIDI serial computer control system. Not only were the pianos wishy-washy in performance, but the chords were "rolled" due to this method of having one command at a time, and the instruments were not "synchronized", as claimed.

George Antheil was correct, even though one must read between the lines in his later revisionist statements about this experimental work. His reference to "chamber music" was right on target. Presented for a small group watching the screen, as in a Parisian Salon, with the Pianola in some form being the center of activities, BALLET MECANIQUE has a mechanical perfection which is not attainable through overblown symphonic treatments, whether solenoid players or human fingers were involved for the keyboard aspects of the work. To recycle BALLET MECANIQUE in this fashion would be similar to taking a string quintet by Boccherini and then dumping it into the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra (with Carmen Dragon, conducting!). The sledgehammer effect would do nothing to improve Boccherini, and it certainly doesn't benefit George Antheil ... no matter how many pianos are spread about the stage!

Now, we'll take a 'break' from the ARTCRAFT Music Roll arrangement and return you to 1925, with an original Pleyel version of Roll III. This will allow you to compare the major perforating differences between the old and the new versions.

Back to Paris of the 'Twenties --